Edward Smith (sea captain)

Edward Smith | |

|---|---|

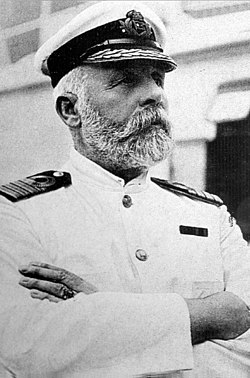

Smith in 1911 | |

| Born | Edward John Smith 27 January 1850 |

| Died | 15 April 1912 (aged 62) |

| Cause of death | Sinking of the Titanic |

| Occupation(s) | Sea captain, naval officer |

| Years active | 1867−1912 |

| Employer | White Star Line |

| Known for | Being the captain of Titanic |

| Spouse |

Sarah E. Pennington (m. 1887) |

| Children | Helen Melville Smith |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Branch | Royal Naval Reserve |

| Rank | Commander |

| Battles / wars | Second Boer War |

Edward John Smith RD RNR (27 January 1850 – 15 April 1912) was a British sea captain and naval officer. In 1880, he joined the White Star Line as an officer, beginning a long career in the British Merchant Navy. Smith went on to serve as the master of numerous White Star Line vessels. During the Second Boer War, he served in the Royal Naval Reserve, transporting British Imperial troops to the Cape Colony. Smith served as captain of the ocean liner Titanic, and perished along with 1,510 others when she sank on her maiden voyage.

Early life

[edit]Edward John Smith was born on 27 January 1850 on Well Street, Hanley, Staffordshire,[1][2] England to Edward Smith, a potter, and Catherine Hancock, born Marsh, who married on 2 August 1841 in Shelton, Staffordshire. His parents later owned a shop.

Smith attended the British School in Etruria, Staffordshire, until the age of 13 when he left and operated a steam hammer at the Etruria Forge. In 1867, he went to Liverpool at the age of 17 in the footsteps of his half-brother Joseph Hancock, a captain on a sailing ship.[3] He began his apprenticeship on Senator Weber, owned by A Gibson & Co. of Liverpool.

On 13 January 1887, Smith married Sarah Eleanor Pennington at St Oswald's Church, Winwick, Lancashire. Their daughter, Helen Melville Smith, was born in Waterloo, Liverpool on 2 April 1898. When the White Star line transferred its transatlantic port from Liverpool to Southampton in 1907, the family moved to a red brick, twin-gabled house, named "Woodhead", on Winn Road, Highfield, Southampton, Hampshire.[4][5]

Family

[edit]Smith's mother, Catherine Hancock, lived in Runcorn, Cheshire, where Smith himself intended to retire. She died there in 1893. Smith's half-sister Thyrza died in 1921 and his widow, Sarah Eleanor Smith, was hit and killed by a taxi in London in 1931.[6] Their daughter, Helen Melville, married and gave birth to twins in 1923, Simon and Priscilla. Simon, a pilot in the Royal Air Force, was killed in 1944, during World War II. Priscilla died from polio three years later; neither of them had children. Helen died in 1973.[2][failed verification]

Career

[edit]Early commands

[edit]Edward Smith joined the White Star Line in March 1880 as the Fourth Officer of SS Celtic.[7] He served aboard the company's liners to Australia and to New York City, where he quickly rose in status. In 1887, he received his first White Star command, the Republic. Smith failed his first navigation exam, but on the next attempt in the following week he passed, and in February 1888, Smith earned his Extra Master's Certificate. Smith joined the Royal Naval Reserve, receiving a commission as a lieutenant, which entitled him to add the letters "RNR" after his name. This meant that in a time of war, he could be called upon to serve in the Royal Navy. His ships had the distinction of being able to fly the Blue Ensign of the RNR; British merchant vessels generally flew the Red Ensign.[8][9][10] Smith retired from the RNR in 1905 with the rank of Commander.

Later commands

[edit]

Smith was Majestic's captain for nine years commencing in 1895. When the Second Boer War broke out in 1899, Majestic was called upon to transport British Imperial troops to the Cape Colony. Smith made two trips to South Africa, both without incident, and in 1903, for his service, King Edward VII awarded him the Transport Medal, showing the "South Africa" clasp. Smith was regarded as a "safe captain". As he rose in seniority, he gained a following amongst passengers with some sailing the Atlantic only on a ship he captained.[11]

Smith even became known as the "Millionaires' Captain".[12] From 1904 on, Smith commanded the White Star Line's newest ships on their maiden voyages. In 1904, he was given command of what was then the largest ship in the world, the Baltic. Her maiden voyage from Liverpool to New York, sailing 29 June 1904, went without incident. After three years with Baltic, Smith was given his second new "big ship", the Adriatic. Once again, the maiden voyage went without incident. During his command of Adriatic, Smith received the long service Decoration for Officers of the Royal Naval Reserve (RD).[13]

As one of the world's most experienced sea captains, Smith was called upon to take first command of the lead ship in a new class of ocean liners, the Olympic – again, the largest vessel in the world at that time. The maiden voyage from Southampton to New York was successfully concluded on 21 June 1911, but as the ship was docking in New York harbour, a small incident took place. Docking at Pier 59 under the command of Captain Smith with the assistance of a harbour pilot, Olympic was being assisted by twelve tugs when one got caught in the backwash of Olympic, spun around, collided with the bigger ship, and for a moment was trapped under Olympic's stern, finally managing to work free and limp to the docks.[citation needed]

Hawke incident

[edit]On 20 September 1911, Olympic's first major mishap occurred during a collision with a British warship, HMS Hawke, in which the warship lost her prow. Although the collision left two of Olympic's compartments filled and one of her propeller shafts twisted, she was able to limp back to Southampton. At the resultant inquiry, the Royal Navy blamed Olympic,[14][15] finding that her massive size generated a suction that pulled Hawke into her side.[16] Captain Smith had been on the bridge during the events.

The Hawke incident was a financial disaster for White Star, and the out-of-service time for the big liner made matters worse. Olympic returned to Belfast and, to speed up the repairs, Harland and Wolff was forced to delay Titanic's completion in order to use one of her propeller shafts and other parts for Olympic. Back at sea in February 1912, Olympic lost a propeller blade and once again returned for emergency repairs. To get her back to service immediately, Harland and Wolff again had to pull resources from Titanic, delaying her maiden voyage from 20 March to 10 April.[citation needed]

Titanic

[edit]Despite the past trouble, Smith was again appointed to command the newest ship in the Olympic class when Titanic left Southampton for her maiden voyage. On March 30, Smith left the Olympic at Southampton, and set out for a quick trip up to Belfast. He arrived there in time to take command of Titanic on April 1.[17] On April 9, as Titanic was docked in Southampton, Smith went ashore and stayed overnight at his home on Winn Road, to spend time with his wife and daughter. Some sources state that he was going to retire after completing Titanic's maiden voyage, in order to spend more time with his family.[a][18]

On 10 April 1912, Smith left his home at 7:00 a.m.. Local paperboy, 11 year old Albert Benham, recalled Smith saying "Alright son, I'll take my paper." He then proceeded to Berth 44, arriving at 7:30 a.m.. At 8:00 a.m., he was onboard Titanic to prepare for the Board of Trade muster. [18] Passenger Norman Wilkinson, acquainted with Smith, asked a quartermaster for Smith's whereabouts; the crewman took him a friend to the Captain, who was then in his cabin. Smith gave Wilkinson a warm welcome but had to admit that he was too busy to conduct them on a personal tour of the liner, instead asking one of the pursers to show them around. On the bridge, Smith got the sailing report from Chief Officer Henry Wilde; Smith finished his paperwork up tidily.[19] After departure at noon, the huge amount of water displaced by Titanic as she passed caused the laid-up New York to break from her moorings and swing towards Titanic. Quick action from Smith helped to avert a premature end to the maiden voyage.

On the evening of April 12, Smith dined with Bruce Ismay in the first class restaurant on B Deck. On the evening of April 13, in the reception room, Smith entertained a party by telling them the "ship could be cut crosswise in three places and each piece would float".[20] On 14 April 1912, Titanic's radio operators[b] received six messages from other ships warning of drifting ice, which passengers on Titanic had begun to notice during the afternoon.

Although the crew was aware of ice in the vicinity, they did not reduce the ship's speed and continued to steam at 22 knots (41 km/h; 25 mph).[21][c] Titanic's high speed in waters where ice had been reported was later criticised as reckless, but it reflected standard maritime practice at the time. According to Fifth Officer Harold Lowe, the custom was "to go ahead and depend upon the lookouts in the crow's nest and the watch on the bridge to 'pick up' the ice in time to avoid hitting it". Lowe, who was crossing the Atlantic for the first time in his life, admitted under examination that he had never heard that icebergs were common off the Grand Banks of Newfoundland and said that the fact would not have interested him if he had. He did not know that the Titanic was following what was called "the southern track", and made a guess that the ship was on the northern one.[23]

The North Atlantic liners prioritised time-keeping above all other considerations, sticking rigidly to a schedule that would guarantee arrival at an advertised time. They were frequently driven at close to their full speed, treating hazard warnings as advisories rather than calls to action. It was widely believed that ice posed little risk; close calls were not uncommon, and even head-on collisions had not been disastrous. In 1907, SS Kronprinz Wilhelm, a German liner, had rammed an iceberg and suffered a crushed bow, but was still able to complete her voyage. That same year Smith declared in an interview that he could not "imagine any condition which would cause a ship to founder. Modern shipbuilding has gone beyond that."[24]

On the morning, Smith personally conducted the services in the First Class Dining Saloon, concluding it with the hymn "Eternal Father, Strong to Save".[25] At 12:45 p.m.., Smith came up onto the bridge. That evening, Smith attended a large dinner party in B Deck restaurant, reportedly held in his honor. Salon Steward Thomas Whiteley stated that Smith talked and joked with John Jacob Astor.[26] At 9:00, Captain Smith conferred with Lightoller on the bridge, and they agreed that they should be able to see an iceberg with plenty of time to avoid it. Smith left the bridge, saying, "If it becomes all doubtful, let me know." At around 10 p.m., Smith went with Fourth Officer Joseph Boxhall to the chart room, where Boxhall gave Smith the ship's position.[27]

At 11:40 p.m. when the ship had just collided with an iceberg, Smith came onto the bridge where he was informed by First Officer William Murdoch of the collision. It was soon apparent that the ship was seriously damaged; Smith asked Boxhall to get designer Thomas Andrews.[28] At around midnight, Smith left the bridge, possibly to make an inspection of the flooding below. He gave a proactive order for the crew to begin uncovering and clearing the boats. Isaac Frauenthal saw Astor approach Captain Smith and tell him, "Captain, my wife is not in good health. She has gone to bed, and I don't want to get her up unless it is absolutely necessary. What is the situation?" Smith advised Astor to awaken his wife, as they might have to take to the boats. Astor "never changed expression...thanked the Captain courteously and walked rapidly, but composedly away". [29] Stewardess Annie Robinson saw him on E Deck, heading towards the Mail Room with a mail clerk and Chief Purser Hugh McElroy. She saw him come back with Andrews and overheard Andrews saying, "Well, three have gone already, Captain"; Smith and Andrews separated, with Smith heading up to the bridge, while Andrews stayed below to continue his inspection. At 12:15, Smith gave another proactive order to swing out lifeboats and to start getting passengers on deck with lifebelts on. He went to the Marconi operators' room and told Junior Marconi Officer Harold Bride and senior wireless operator John "Jack" Phillips to get ready to send out a call for assistance. He went up and down on deck, telling passengers to put lifebelts on.[30] At 12:25, Andrews reported to Smith that all of the first five of the ship's compartments had been breached and that Titanic would sink in under two hours. Captain Smith was an experienced seaman who had served for 40 years at sea, including 27 years in command. This was the first crisis of his career, and he would have known that even if all the boats were fully occupied, more than a thousand people would remain on the ship as she went down, with little or no chance of survival.

Although myths say that Smith was very ineffective and inactive in preventing loss of life, and became paralysed by indecision, had a mental breakdown or nervous collapse, and was lost in a trance-like daze, being ineffective and inactive in attempting to mitigate the loss of life,[31][32][33][32][34] this is disputed by careful research of eyewitness accounts which describe Smith as taking charge and behaved coolly and calmly during the crisis. He had immediately began an investigation into the nature and extent of the damage, personally making two inspection trips below deck to look for damage, and preparing the wireless men for the possibility of having to call for help. He erred on the side of caution by ordering his crew to begin preparing the lifeboats for loading, and to get the passengers into their lifebelts before he was told by Andrews that the ship was sinking. Smith was observed all around the decks, personally overseeing and helping to load the lifeboats, interacting with passengers, and trying to instil urgency to follow evacuation orders while avoiding panic.[35] After the talk with Andrews, Smith gave the order to begin loading women and children into the boats. He told Boxhall that the ship would sink. Second Officer Lightoller recalled afterwards that he had to cup both hands over Smith's ears to communicate over the racket of escaping steam, and said, "I yelled at the top of my voice, 'Hadn't we better get the women and children into the boats, sir?' He heard me and nodded reply." Smith then ordered Lightoller and Murdoch to "put the women and children in and lower away"[36] He ordered passengers down to the Promenade Deck to begin boarding Boat No. 4; he personally assisted in the loadings of Boats No 8, 6, and 2, where he ordered Major Arthur Godfrey Peuchen of the Royal Canadian Yacht Club in.[37] He also checked in on the bridge with Boxhall to fire rockets. When passenger Eloise Hughes Smith (no relation) pleaded whether Lucian, her husband of two months, could go with her, Captain Smith ignored her, shouting again through his megaphone the message of women and children first.[38]

Just minutes before the ship started its final plunge, Smith was still busy releasing Titanic's crew from their duties; he went to the Marconi operators' room and released Bride and Phillips from their duties. He then carried out a final tour of the deck, telling crew members: "Now it's every man for himself."[39] At 2:10 a.m., as Steward Edward Brown assisted men in attempting to launch collapsible boat A, the captain approached with a megaphone in his hand, saying, "Well, boys, do your best for the women and children, and look out for yourselves."[d] Brown saw Smith return to the bridge alone.[41][42] A few minutes later, Trimmer Samuel Hemming found the bridge apparently empty.[43] At 2:20 a.m., Titanic sank. Smith perished along with around 1,500 others; his body was never recovered.

Death

[edit]Conflicting accounts of Smith's death emerged following the disaster.[44] Initial rumours claimed that Smith shot himself.[45] Some press accounts suggest that Smith remained on the bridge and went down with his ship.[46][47] The New York Herald in its 19 April 1912 edition quoted Robert Williams Daniel as having seen Smith on the bridge, waist high in water.[48][49] Daniel's account is unlikely as he jumped from the stern as the ship sank.[50]

Captain Smith himself made statements hinting that he would go down with his ship if he was ever confronted with a disaster. A friend of Smith's, Dr. Williams, asked Captain Smith what would happen if the Adriatic struck a concealed reef of ice and was badly damaged. "Some of us would go to the bottom with the ship," was Smith's reply. A boyhood friend, William Jones said, "Ted Smith passed away just as he would have loved to do. To stand on the bridge of his vessel and go down with her was characteristic of all his actions when we were boys together."[51] This popular belief, thereby perpetuated – has been portrayed in various portrayals of the disaster, such as the 1958 film A Night to Remember and the 1997 film Titanic.[50]

Alternatively, Smith may have jumped overboard from the bridge—and after entering the bridge from the starboard side—in order to give the command to abandon the ship to crew on the port side. When working to free Collapsible B, Junior Marconi Officer Harold Bride said he saw Captain Smith dive from the bridge into the sea just as Collapsible B was levered off the roof of the officers' quarters,[52] Tim Maltin suggests Bride "could here be mistaking Captain Smith for Lightoller, who we know did exactly this at this time, first swimming towards the crow's nest."[53] However, first class passenger Mrs Eleanor Widener, who was in Lifeboat No. 4 (the closest to the sinking ship) at the time,[54] and second class passenger William John Mellors, who survived aboard Collapsible B, stated that Smith jumped from the bridge. [55] Second Class Passenger William Mellors, however also claimed to have seen Smith leap from the bridge. In addition, mess steward Cecil Fitzpatrick claimed to have seen Smith on the bridge just a few minutes before the ship began its final plunge. He was said to be with Andrews. The two put on lifebelts; Smith told Andrews, "We cannot stay any longer; she is going!" Fitzpatrick saw Andrews and Smith both jump overboard just as the water reached the bridge.[56]

Moreover, there is circumstantial evidence to suggest that Smith may have perished in the water near the overturned Collapsible B. Colonel Archibald Gracie reported that an unknown swimmer came near the capsized and overcrowded lifeboat and that one of the men on board told him "Hold on to what you have, old boy. One more of you aboard would sink us all"; in a powerful voice, the swimmer replied "All right boys. Good luck and God bless you.".[57][58][59] The man never asked to come aboard the boat, but instead cheered its occupants saying "Good boys! Good lads!" with "the voice of authority".[60] One of the Collapsible B survivors, fireman Walter Hurst, tried to reach him with an oar, but the man had died.[60] Hurst said he was certain this man was Smith.[60] Gracie said he heard men, including stoker Harry Senior and Entree cook Isaac Maynard, on collapsible B say that Captain Smith was the swimmer.[61] Some of these accounts also describe Smith carrying a child to the boat, with press reports saying that Maynard had retrieved a baby from the captain.[55][62] No baby was saved from Collapsible B, and second class passenger Elizabeth Nye gave a press interview saying she had heard the child had died.[35] Smith's wife later expressed her belief in the story of Smith saving a child.[63] Lightoller, who survived on Collapsible B, never reported seeing Smith in the water or receiving a child from him. Some have questioned as to whether based on the wordings, if survivors on Collapsible B would have been able to verify an individual's identity under such dimly lit and chaotic circumstances, and debate whether it wishful thinking that it was the Captain.[64]

Legacy

[edit]

Eleanor Smith wrote a letter of condolence to family members and friends of those who perished in the sinking, posted outside the White Star Line officers in London on April 18: "To my poor fellow sufferers: My heart overflows with grief for you. I am laden with sorrow that you should be weighed down with this terrible burden that has been thrust upon us. I pray God will comfort all."[65]

A statue of Smith, sculpted by Kathleen Scott, widow of Antarctic explorer Robert Falcon Scott, was unveiled in July 1914 at the western end of the Museum Gardens in Beacon Park, Lichfield.[66] The pedestal is made from Cornish granite and the figure is bronze.[67] Lichfield was chosen as the location for the monument because Smith was a Staffordshire man and Lichfield was the centre of the diocese.[68] The statue originally cost £740 (£90,000 with inflation[69]) raised through local and national contributions.[68]

In 2010, as part of the "Parks for People" programme, the statue was restored and the green patina removed from its surface at a cost of £16,000.[68] In 2011 an unsuccessful campaign was started to get the statue moved to Captain Smith's home town of Hanley.[70]

Smith had already been commemorated in Hanley Town Hall with a plaque reading: "This tablet is dedicated to the memory of Commander Edward John Smith RD, RNR. Born in Hanley, 27th Jany 1850, died at sea, 15th April 1912. Whilst in command of the White Star SS Titanic that great ship struck an iceberg in the Atlantic Ocean during the night and speedily sank with nearly all who were on board. Captain Smith having done all man could do for the safety of passengers and crew remained at his post on the sinking ship until the end. His last message to the crew was 'Be British.'"[71]

The plaque was removed in 1961, given to a local school and then returned to the Town Hall but remounted in the interior of the building in 1978.[72] The Titanic Brewery in Burslem, Stoke-on-Trent, is in honour of him.[73]

As a member of the Royal Naval Reserve, Smith wore his two decorations when in uniform: the Decoration for Officers of the Royal Naval Reserve and the Transport Medal.

Portrayals

[edit]- Otto Rippert (1912) In Nacht und Eis

- Otto Wernicke (1943) (Titanic)

- Brian Aherne (1953) (Titanic)

- Clarence Derwent (1956) (Kraft Television Theatre) (A Night to Remember)

- Laurence Naismith (1958) (A Night to Remember)

- Michael Rennie (1966) (The Time Tunnel, episode Rendezvous With Yesterday) (fictionalised as "Captain Malcolm Smith")

- Harry Andrews (1979) (S.O.S. Titanic) (TV Movie)

- Hugh Reilly (1983) (Voyagers!) (Voyagers of the Titanic)

- George C. Scott (1996) (Titanic) (TV Miniseries)

- John Cunningham (1997) (Titanic) (Broadway Musical)

- Bernard Hill (1997) (Titanic)

- Kenneth Belton (2001) (Titanic: The Legend Goes On) (Animated Film)

- John Donovan (2003) (Ghosts of the Abyss) (Documentary)

- Alan Rothwell (2005) (Titanic: Birth of a Legend) (TV Documentary)

- Malcolm Tierney (2008) (Who Sank the Titanic? aka The Unsinkable Titanic) (TV Documentary)

- Christian Rodska (2011) (Curiosity, episode: "What Sank Titanic?") (TV episode)

- David Calder (2012) (Titanic) (TV series/4 episodes)

- Philip Rham (Titanic - The Musical) (Southwark Playhouse, 2013, and Charing Cross Theatre, London, 2016)

- Xander Bailey (2022) (Titanic 666) (TV movie)

Bibliography

[edit]- Titanic Captain: The Life of Edward John Smith, G.J. Cooper. ISBN 978-0-7524-6072-7, The History Press Ltd, 2011.

- Fitch, Tad; Layton, J. Kent; Wormstedt, Bill (2012). On A Sea of Glass: The Life & Loss of the R.M.S. Titanic. Amberley Books. ISBN 978-1848689275.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Although two press stories in the Halifax Morning Chronicle published after the disaster reported that Smith would have remained in charge of Titanic "until the Company (White Star Line) completed a larger and finer steamer", the reference is regarded as vague, casting shadow of suspicion on the sources were, despite purportedly coming from White Star Officials.

- ^ Radio telegraphy was known as "wireless" in the British English of the period.

- ^ Despite the later myth, featured for example in the 1997 film Titanic, the ship Titanic was not attempting to set a transatlantic speed record; the White Star Line had made a conscious decision not to compete with their rivals Cunard on speed, but instead to focus on size and luxury.[22]

- ^ Some press reports would claim that Smith advised crewmen with the words "Be British, boys. Be British!" Not one of the surviving crew members claimed he uttered such words, and this is regarded as a myth.[40]

References

[edit]- ^ "We Are Stoke-on-Trent: What links the Titanic and oatcakes?". BBC News. 29 September 2019. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- ^ a b "Plaque for Titanic captain's house in Stoke-on-Trent". BBC News. 20 March 2012. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- ^ Kasprzak, Emma (15 March 2012). "Titanic: Captain Edward John Smith's legacy". BBC News. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- ^ Kerins, Dan (10 January 2012). "Captain Edward J. Smith's home, 34 Winn Road, Highfield, Southampton". The Daily Echo. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- ^ Barczewski, S.L. (2004). Titanic: A Night Remembered. Hambledon and London. p. 165. ISBN 978-1-85285-434-8. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

when White Star moved its main port of embarcation to Southampton in 1907 they followed, settling into a large red brick house on Winn Road

- ^ Cooper, Gary (31 October 2011). Titanic Captain: The Life of Edward John Smith. History Press Limited. pp. 300–. ISBN 978-0-7524-6777-1.

In 1931, Eleanor was ... knocked down by a taxi cab in Cromwell Road, dying a short while ... A verdict of accidental death was returned by the coroner.

- ^ Behe, George (29 February 2012). On Board RMS Titanic: Memories of the Maiden Voyage. The History Press. ISBN 9780752483054.

- ^ Naval Staff Directorate. "Naval Flags and Ensigns" (PDF). p. 12. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 June 2014. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- ^ "Titanic Captain • Titanic Facts". 4 June 2018. Retrieved 7 February 2023.

- ^ Owner, Practical Boat (20 September 2012). "Titanic captain originally failed his navigation test". Practical Boat Owner. Retrieved 7 February 2023.

- ^ Butler, Daniel Allen (2012). Unsinkable: The Full Story. Frontline Books. pp. 47–48. ISBN 9781848326415.

- ^ Cashman, Sean Dennis (1998). America Ascendant: From Theodore Roosevelt to FDR. NYU Press. p. 136. ISBN 9780814715666.

- ^ Gary Cooper (2011). Titanic Captain: The Life of Edward John Smith. p. 133. The History Press

- ^ Bonner, Kit; Carolyn Bonner (2003). Great Ship Disasters. MBI Publishing Company. pp. 33–34. ISBN 978-0-7603-1336-7.

- ^ Gibbons, Elizabeth. "To the Bitter End". williammurdoch.net. Retrieved 4 November 2018.

- ^ "Why A Huge Liner Runs Amuck". Popular Mechanics. Hearst Magazines. February 1932.

- ^ Fitch, Layton & Wormstedt 2012, p. 49.

- ^ a b Fitch, Layton & Wormstedt 2012, p. 60-61.

- ^ Fitch, Layton & Wormstedt 2012, p. 73-74.

- ^ Fitch, Layton & Wormstedt 2012, p. 111-113.

- ^ Ryan 1985, p. 10.

- ^ Bartlett 2011, p. 24.

- ^ Mowbray 1912, p. 278.

- ^ Barczewski 2006, p. 13.

- ^ Fitch, Layton & Wormstedt 2012, p. 115-116.

- ^ Fitch, Layton & Wormstedt 2012, p. 130.

- ^ Fitch, Layton & Wormstedt 2012, p. 133-135.

- ^ Fitch, Layton & Wormstedt 2012, p. 156.

- ^ Fitch, Layton & Wormstedt 2012, p. 163–166.

- ^ Fitch, Layton & Wormstedt 2012, p. 170.

- ^ Ballard & Archbold 1987, p. 22.

- ^ a b Butler 1998, pp. 250–52.

- ^ Bartlett 2011, p. 106.

- ^ Cox 1999, pp. 50–52.

- ^ a b Fitch, Layton & Wormstedt 2012, p. 162-163.

- ^ Fitch, Layton & Wormstedt 2012, p. 183-163.

- ^ Testimony of Arthur G. Peuchen at Titanic inquiry.com

- ^ Statement of Mrs. Lucian P. Smith at the US Inquiry

- ^ Butler, Daniel Allen (1998). Unsinkable: The Full Story of RMS Titanic. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-8117-1814-1.

- ^ Howells, R. (1999). "5 - 'Be British!'". The Myth of the Titanic. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 99–119. ISBN 9780230510845. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

[page 101]The historical evidence that Smith ever actually said "Be British!" is actually very slight indeed ... myths frequently conform to cultural wishes and expectations rather than documentary evidence.

- ^ "British Wreck Commissioner's Inquiry. Day 9". Titanic Inquiry.

- ^ Formal Investigation Into the Loss of the S.S. "Titanic": Evidence, Appendices, and Index, Volume 3. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office. 1912. p. 220. ISBN 9780115004988. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Testimony of Samuel Hemming at Titanic inquiry.com

- ^ On A Sea of Glass: The Life & Loss of the R.M.S. Titanic (Tad Fitch, J. Kent Layton and Bill Wormstedt), Appendix M: "Down With the Ship? Captain Smith's Fate", ISBN 1848689276), pg. 323.

- ^ "Capt. Smith Ended Life When Titanic Began To Founder (Washington Times)". Encyclopedia Titanica. 19 April 1912. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- ^ Ballard & Archbold (1987), pp. 40–41; Chirnside (2004), p. 177.

- ^ Daniel Allen Butler suggests Smith entered the wheelhouse on the bridge, to await his end.: "if Smith did indeed go to the bridge around 2:10 a.m. as Steward Brown said, and took refuge inside the wheelhouse, that would explain why Trimmer Hemming did not see him when he went onto the bridge a few minutes later. Earlier, at nightfall, the shutters on the Titanic's wheelhouse windows would have been raised, to keep the lights of the wheelhouse from interfering with the bridge officers' night vision: Trimmer Hemming would have been unable to see Captain Smith had the captain indeed been inside the wheelhouse, awaiting his end". (website)

- ^ Spignesi, Stephen (2012). The Titanic for Dummies. John Wiley & Sons. p. 207. ISBN 9781118206508. Retrieved 6 November 2012.

- ^ "Robert Williams Daniel | William Murdoch". www.williammurdoch.net.

- ^ a b Fitch, Layton & Wormstedt 2012, p. 326.

- ^ On a Sea of Glass: the life and loss of the RMS Titanic. by Tad Fitch, J. Kent Layton & Bill Wormstedt. Amberley Books, March 2012. pp 329-334

- ^ "TIP | United States Senate Inquiry | Day 14 | Testimony of Harold S. Bride, recalled". www.titanicinquiry.org.

- ^ Maltin, Tim; Aston, Eloise (2011). "#83 Captain Smith Committed Suicide As the Ship Went Down". 101 Things You Thought You Knew About the Titanic . . . but Didn't! (E-book ed.). Penguin. ISBN 9781101558935.

- ^ "Mrs. Eleanor Widener | William Murdoch". www.williammurdoch.net.

- ^ a b "Secondary accounts - no mention of an officer's suicide (from Logan Marshall's Sinking of the Titanic and Great Sea Disasters)". Bill Wormstedt's Titanic. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

Captain Smith … did not shoot himself," ... "jumped from the bridge.

- ^ Fitch, Layton & Wormstedt 2012, p. 329.

- ^ Gracie, Archibald (7 August 2012). The Truth About the Titanic. Tales End Press. ISBN 9781623580254 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Cries in the Night". 19 September 2000. Archived from the original on 19 September 2000. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- ^ "Captain Edward John Smith". Archived from the original on 22 August 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ^ a b c Lord, Walter (6 March 2012). A Night to Remember: The Sinking of the Titanic. Open Road Media. ISBN 9781453238417 – via Google Books.

- ^ Gracie 1913, p. 95.

- ^ Lord 2005, p. 98.

- ^ "Letter from Captain Smith's Widow". encyclopedia-titanica.org. 6 June 1912. Retrieved 14 May 2025.

- ^ "Charles Eugene Williams | William Murdoch". www.williammurdoch.net.

- ^ "Wife of Titanic captain conveys sympathies - UPI Archives".

- ^ "Smith information at". Titanic-titanic.com. Archived from the original on 15 January 2010. Retrieved 6 November 2012.

- ^ Noszlopy, George T. (2005), Public Sculpture in Staffordshire & the Black Country, Liverpool University Press, ISBN 978-0-85323-999-4

- ^ a b c Kerr, Andy (3 November 2011). "Captain of the Titanic is here to stay despite no local connection". Lichfield Mercury. Lichfield. p. 29.

- ^ UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ "Titanic Captain Smith statue Hanley move campaign", BBC News, 26 August 2011, retrieved 26 August 2011

- ^ Barczewski 2006, pp. 172–173.

- ^ Barczewski 2006, p. 175.

- ^ "Titanic Brewer" Archived 15 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine. titanicbrewery.co.uk

Sources

[edit]- Ballard, Robert D.; Archbold, Rick (1987). The Discovery of the Titanic. Madison Pub. ISBN 978-0-670-81917-1.

- Barczewski, Stephanie (2006). Titanic: A Night Remembered. London: Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-85285-500-0.

- Bartlett, W.B. (2011). Titanic: 9 Hours to Hell, the Survivors' Story. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4456-0482-4.

- Chirnside, Mark (2004). The Olympic-class Ships: Olympic, Titanic, Britannic. Tempus. ISBN 978-0-7524-2868-0.

- Cox, Stephen (1999). The Titanic Story: Hard Choices, Dangerous Decisions. Chicago: Open Court Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8126-9396-6.

- Gracie, Colonel Archibald (1913). The Truth About the Titanic. New York: Mitchell Kennerley.

- Mowbray, Jay Henry (1912). Sinking of the Titanic. Harrisburg, PA: The Minter Company. OCLC 9176732.

- Ryan, Paul R. (Winter 1985–1986). "The Titanic Tale". Oceanus. 4 (28). Woods Hole, MA: Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

See also

[edit]External links

[edit]- 1850 births

- 1912 deaths

- 19th-century Royal Navy personnel

- 20th-century Royal Navy personnel

- 19th-century English people

- 20th-century English people

- British Merchant Navy officers

- British Merchant Navy personnel

- British military personnel of the Second Boer War

- Captains who went down with the ship

- Deaths on the RMS Titanic

- English sailors

- Military personnel from Stoke-on-Trent

- People from Hanley, Staffordshire

- People from Southampton

- Royal Naval Reserve personnel

- Royal Navy officers

- Steamship captains

- Ship captains of the White Star Line