Awjila

Awjila

أوجله Augila and Wajulo | |

|---|---|

Town | |

A farm in Awjilah | |

| Coordinates: 29°6′29″N 21°17′13″E / 29.10806°N 21.28694°E | |

| Country | |

| Region | Cyrenaica |

| District | Al Wahat |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| License Plate Code | 67 |

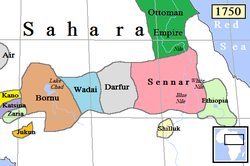

Awjila (Arabic: أوجلة; Latin: Augila) is an oasis town in the Al Wahat District in the Cyrenaica region of northeastern Libya. Since classical times, it has been known as a place where high-quality dates are farmed. The oasis was mentioned by the Greek historian Herodotus (c. 484–425 BCE), who referred to it as Augila.[1] Historically, Awjila was one of the ancient homelands of the Toubou (Gara'an), an Indigenous people, and was abandoned following Berbers (Tuareg-Amazagh) invasion that occurred long before Herodotus’s time. The name Augila derives from the Toubou term Wajulo, meaning 'the low'—that is, lowland—and preserves the oasis’s Indigenous linguistic heritage.The oases of Awjila, Julo and Jakhara are all of Toubou origin and were also collectively referred to as Wajula in Toubou, meaning 'the lows,' i.e., lowlands. Awjila was the capital of this district, and the term Wajula also denote the people of Aguila—Augilians—as well as, more broadly, the inhabitants of the whole district.[2] Since the Arab conquest in the 7th century, Islam has played an important role in the community. The oasis is located on the east-west caravan route between Egypt and Tripoli, Libya, and the north-south route between Benghazi and the Sahel between Lake Chad and Darfur. In the past, it was an important trading center. The people cultivate small gardens using water from deep wells. Recently, the oil industry has become an increasingly important source of employment.

Location

[edit]Awjila and the adjoining oasis of Jalu are isolated, the only towns on the desert highway between Ajdabiya, 250 kilometres (160 mi) to the northwest, and Kufra, 625 kilometres (388 mi) to the southeast.[3] An 1872 account describes the cluster of three oases: the Aujilah oasis, Jalloo (Jalu) to the east and Leshkerreh (Jikharra) to the northeast. Each oasis had a small hill covered in date palm trees, surrounded by a plain of red sand impregnated with salts of soda.[4] Among them, the three oases had a population of 9,000 to 10,000 people.[4] The people of the oasis are mainly Amazigh, and some still speak a Amazigh-origin language.[5] As of 2005, the Awjila language was highly endangered.[6]

Climate

[edit]| Climate data for Awjila | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 19.9 (67.8) |

21.9 (71.4) |

25.3 (77.5) |

29.7 (85.5) |

34.7 (94.5) |

37.2 (99.0) |

36.7 (98.1) |

36.9 (98.4) |

35.8 (96.4) |

32.4 (90.3) |

27.0 (80.6) |

21.4 (70.5) |

29.9 (85.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 5.6 (42.1) |

7.0 (44.6) |

9.2 (48.6) |

13.1 (55.6) |

18.3 (64.9) |

19.9 (67.8) |

21.0 (69.8) |

21.0 (69.8) |

19.9 (67.8) |

16.3 (61.3) |

12.0 (53.6) |

7.7 (45.9) |

14.3 (57.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 3 (0.1) |

3 (0.1) |

3 (0.1) |

2 (0.1) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

3 (0.1) |

2 (0.1) |

3 (0.1) |

19 (0.7) |

| Source: Climate-data.org | |||||||||||||

History

[edit]Classical times

[edit]The oasis is mentioned by Herodotus, who also describes the nomadic Nasamones, a Amazigh tribe, migrating in fixed seasons between the coasts of Syrtis Major (Gulf of Sirte) and the Augila oasis. According to Herodotus, it was a journey of ten days from the oasis of Ammonium—modern-day Siwa—to the oasis of Augila, where men live around a spring of water.[1] The people Herodotus described as living around this spring were the ancestors of the Berbers, including the Tuareg and Amazigh. Historians trace the origins of the Berbers (Tuareg) Sultanate of Aïr (in present-day Niger) to four tribes—the Iteseyen, Jedalanan, Azaranan, and Afadanan—that migrated from Awjila and reached the Aïr region around the 11th century. After displacing the indigenous Hausa populations from their lands, they lived without a sultan for a very long time until 1404 CE, when five tribes collectively known as the Imakitan appointed their first sultan.[7][8] These successive waves of migration and conquest help explain some of the ethnic distortions and historical confusions found in Herodotus’s accounts. His descriptions of the Garamantes—the ancestors of the Toubou (the Toubou, also known as Gara'an—this name is used in Sudan and some parts of Chad to refer to the Toubou and ascribed to them through their Garamantic ancestors. In fact, these names are used interchangeably throughout the Toubou world)—were filtered through reinterpretations by these Berbers (Tuareg-Amazagh), contributing to the inconsistencies and ambiguities in classical sources. A comparable example is the case of the Psylli, a Berber (Amazigh) tribe said to have been buried by a strong desert sandstorm during the time of Herodotus. According to him, they perished when the force of the south wind dried up their water tanks, leaving their land—located in the region of the Syrtis—completely waterless. After deliberating, the Psylli decided to march south. As Herodotus notes, "I tell the story as it is told by the Libyans," indicating his reluctance to confirm its accuracy—something common in his accounts. Upon entering the sandy desert, they were overwhelmed and buried by a strong south wind, leading to their complete destruction. Their territory was subsequently taken over by the Nasamones. However, the Psylli later reappear in Natural History (c. 77 CE) by Pliny the Elder, where they are recorded as being in conflict with the Nasamones.[9][10]

The distance from Siwa (ancient Ammonium) to Awjila was confirmed by the German explorer Friedrich Hornemann (1772–1801), who traveled the route in 1799, covering the journey in 11 days. Hornemann recorded information from the inhabitants of Awjila, primarily Berbers—who are the ancestors of the present-day Tuareg and Amazigh peoples—who informed him that Febabo (the ancient Toubou name for present-day Kufra Oasis) lay approximately ten days' journey to the south, averaging around twenty-one miles per day. They also noted that no water could be found during the first six days of travel from Awjila toward Kufra.[11] According to local informants, the caravan journey from Siwa to Awjila usually takes 13 days.

In addition, Friedrich Hornemann recorded that the inhabitants (Berbers) of Awjila, described the language of the Toubou as resembling "the whistling of birds." This description closely mirrors the second passage of Herodotus about the Garamantes (Histories, Book IV, page 184), reported that the Garamantes spoke in a manner “like the whistling of bats or birds.” Hornemann noted that the Berbers of Awjila used identical phrasing when describing the Toubou tribes, strongly showing that Herodotus's account was clearly influenced by Berber informants from this region. This also implies that Herodotus has been unaware of the indigenous identity of the Garamantes (Toubou) in Awjila, as well as the meaning of the name "Awjila" itself—information that have been obscured, much like the case of the Psylli tribe. The repetition of such specific language in both ancient and later sources strongly shows a shared narrative tradition originating from people of Awjila, which lies geographically close to key Garamantian (Toubou's ancestors) settlements, notably the Zella Oasis in the Jufrah district—one of the ancient homelands of the Toubou which is also mentioned by Herodotus a ten day from Awjila. This proximity raises the possibility that Berber intermediaries shaped or reframed aspects of Garamantian history to align with their own oral traditions or political narratives. Within this context, the portrayal of the Garamantes as deliberately rudimentary or linguistically obscure clearly reflects the distortions introduced through second-hand reporting rather than an accurate ethnographic account.[12]

Some scholars, such as Oric Bates in The Eastern Libyans, have questioned the reliability of Herodotus’s descriptions—particularly his claims that the Garamantes “shun the sight and fellowship of men,” possess “no weapons of war,” and are characterized by general “ignorance.” Also, Bates argues that two passages by Herodotus are corrupted. These portrayals are clear distortions arising from secondhand reports mediated by local informants, specifically the people of Awjila—ancestors of the Tuareg-Amazigh (Berbers)—rather than from direct observation. Such early inaccuracies were later echoed and elaborated upon by other writers, most notably the Roman author Pliny the Elder. Pliny and others introduced a fictitious group called the Gamphasantes as discussed in Bates p. 53, seemingly invented to reconcile the contradictions within Herodotus’s narrative.[13]

Pliny also pointed out a place where the precious stones known as carbuncles—highly valued by the Romans and the ancient world—were produced and traded through interactions with the Troglodytae (Aethiopians), i.e., the Garamantes, who transported these stones from Ethiopia (Africa).[14] The terms “Troglodytae” and “Aethiopians” were often used interchangeably by ancient writers and frequently referred to the Garamantes as either Troglodytae, Aethiopians or both—i.e., as “Troglodytaean Aethiopians” (meaning Blacks). As Bates notes (The Eastern Libyans, p. 53), the northern Fezzan region (modern-day Jufra) was inhabited by Troglodytic Aethiopians—who were, in fact, the Garamantes. Herodotus places the Garamantes approximately ten days’ journey from Awjila, which corresponds precisely to the Zella Oasis or the broader Jufra district. As stated by Oric Bates, these two passages in Herodotus were corrupted as a result of deliberate distortion by his local Berber (Tuareg-Amazigh) informants—manipulations that remain evident upon close analysis.[13]

Furthermore, Pliny elaborated on Herodotus’s second passage concerning the Troglodytae Ethiopians, stating that they hollowed out caverns to live in and they have no voice—only making noises—being entirely devoid of intercourse by speech. These claims, among other details, were clearly borrowed from Herodotus’s account. However, Pliny also noted that the Romans engaged in trade with the Troglodytae to acquire the precious stones known as carbuncles as seen above. These implausible details further contributed to a distorted portrayal based on Herodotus’s secondhand reports rather than direct ethnographic observation.[15] Pliny also references tribes and place names corresponding to actual Toubou (Garamantes) populations encountered during the Balbus expedition in Fezzan against the Garamantes in the 19 BC—including the Alele, Balla, Buluba, Maxalla and Tamaigi tribes, among many others. This suggests that while Pliny had access to genuine ethnographic material, it was often interwoven with apocryphal or distorted accounts inherited from Herodotus that shaped by local informants.[16]

Few historians have subjected Herodotus’s claims to serious critical examination. For the most part, later writers uncritically repeated his accounts, allowing inaccuracies and distortions to persist over the centuries. It was only during the mid-20th century that a limited number of scholars—particularly some German or Austrians historians—undertook more rigorous and critical analyses of Herodotus’s descriptions, challenging long-standing assumptions and emphasizing the need for evidence-based interpretations. When these historians conducted field investigations in the Tibesti region, they found no evidence supporting the idea that the Toubou lived in caves there. Instead, caves were used only as temporary shelters or resting points during long desert journeys. The researchers found no signs of permanent or long human habitation, such as smoke stains on cave ceilings or tools embedded in the ground. Additionally, most Toubou tribes migrated into the Tibesti region relatively recently, between the 15th and 18th centuries, initially fleeing punitive campaigns conducted by the Kanem-Bornu kings. Subsequent waves of displacement occurred during the 19th century from the Jalu Oasis and Cyrenaica more broadly, as a result of Arab invasions aided by the Ottoman Empire during the reign of Yusuf Pasha Karamanli (1795–1832), the governor of Tripoli.[2]

Moreover, the Tehenu (Temehu), ancient Libyan tribal groups, were among the earliest inhabitants of the Mediterranean basin at the end of the Old Stone Age. They were present throughout the Mediterranean coastlines and are the direct ancestors of the Garamantes—themselves the forebears of the Toubou. These nations are distinct from the Berbers and MUST NOT be conflated with them. Haynes appears unaware of the ancestral connection, due to the distortions and omissions introduced by Eurocentric scholars. He even acknowledged that a significant problem needs to be resolved. Consequently, in response to these Eurocentric biases, recent research has clarified the ancestral connections and corrected earlier distortions and established the true facts.[17][18] The names Tehenu and Temehu mean “Southern land” and “Eastern land,” respectively. In both terms, Te means “land,” while henu means “south” and mehu means “east.” This distinction is also confirmed by historical sources, including Oric Bates, who observed that the names correspond to specific geographical regions. these interpretations are supported by linguistic and geographical evidence, as acknowledged by other historians as well.[18]

Eurocentric narratives have deliberately distorted the origins of the Tehenu by intentionally claiming that their name means "olive oil" or "land of olives." while, the Temehu—a clearly defined branch of the Tehenu, as noted by Oric Bates and other scholars—were misrepresented by figures such as Gerald Massey in A Book of the Beginnings. Massey claimed that their name meant "created white," interpreting Tama as "created" or "people" and hu as "white," hence "created white" fair as Europeans. Some others even asserted that they had blue eyes and blond hair. These claims, however, are completely unsupported by credible historical evidence. In reality, ancient wall depictions clearly confirm and also historically that both the Tehenu and Temehu were Black people and one nation.

The Libyan Pharaoh Sheshonq I, founder of Egypt's 22nd Dynasty, was of Tehenu origin, as explicitly stated on the stela of Pasenhor. The inscription also names his grandfather, Buyu-Wawa, and other family members with names of significant meanings and the same this family of descented from Buyu-Wawa also ruled the 23 dynasty—for instance, Iyubut (also spelled Auput), meaning "Man of Status," where the "T" signifies "of," and Bami (Pamey), which means "Son of Men of Status." Despite such clear links, Eurocentric narratives have attempted to obscure the origins of the Tehenu, who were the founders of Egypt’s 22nd and 23rd Dynasties. The Tehenu also were the first Libyan people to be mentioned in Egyptian records, dating back to the Old Kingdom. They were virtually indistinguishable from the Egyptians themselves, occupying high-ranking military positions and playing an integral role in Egyptian society as well as Egyptian records used the terms Tehenu and Temehu interchangeably, referring to the same people.[18] Scholars like Oric Bates—similar to Haynes—appear to have misunderstood or overlooked the true identities and legacy of the Tehenu, the Garamantes, and the Toubou. Notably, the Tehenu gave rise to rulers who ascended to the Egyptian throne during the 22nd and 23rd dynasties.[18][2]

Sheshonq’s title, "Great Chief of the Ma," literally means the "Great Chief of the Noble Rulers (Mais)". Here, "Ma" (anglicized Mais) is the plural form of "Mai," the official title for Kanem-Bornu kings. For instance, the king of the Duguwa dynasty was called Boyo-Ma, meaning "The Big of the Noble Rulers (Mais)," while Sheshonq’s grandfather Boyo-Wawa means The Big of the Wawa areas. The Wawa areas include Waw al-Namous, Waw al-Kabir, Tuma (= Temehu) is located in Fazzen near the Niger border and many other place names, and places in Chad such as in Tibesti Wari, Waria, Zower, Zowerga, and Taanoa (= Tehenu) is located Fazzen between Chad and Libya and many more other place names. All these place names refer to as a series of Wawa areas in Toubou. The Kanem-Bornu Empire is a Toubou empire, and the royal family of the empire is of Toubou origin. This title Ma further confirms the shared origin of the Kanem-Bornu Kings.[18][2] Additionally, the name Boyo (Buyu), as noted by Palmer, along with the word Mâ are of purely Toubou origin. Variations such as ama, am and ma—synonymous with ana, an and na—all mean "people." Typically, Ama and Ana are used as prefixes, while the others function as suffixes. The word Ma, in particular, carries several meanings depending on the context, including "human"—for example, in the name Shiruma, which means "difficult human"—as well as "sons," "noble ruler," "noble rulers," or simply "ruler," "rulers," "noble," and "nobles." While Palmer’s work addresses some of these meanings, it does not fully cover all aspects, including certain tribal origins. Nevertheless, his research remains valuable, and these gaps are relatively minor.[19] The name Akakus mountains is of Toubou origin and many others.

The name Gara'an—another name for the Toubou—is ascribed to them through their Garamantian ancestors. The term Garamantes originates from Gara'ma—ntes (equivalent to Gara'an), meaning "Ga-speaking people." The Daza-Ga and Teda-Ga speakers were anciently referred to as Gara (the original Kushites), their designation meaning "Ga-speakers," while ma (equivalent to an) signifies "people." Hence, Garamantes essentially means "Ga-speaking people." Similarly, the name Toubou follows a structure comparable to that of their ancestors, the Tehenu (Temehu). The first syllable Tu in Toubou means "land," just like the prefixes Ta, Te, and Ti, which all carry the same meaning. The second syllable Bu literally means "Big," however, also conveys extended meanings such as "Grand" or "Great." Therefore, in this linguistic and cultural context, Toubou can be interpreted as "The Grand Land" or "The Great Land," reflecting the vast territory they once inhabited, have historically lived in, and continue to inhabit today—spanning Libya, Chad, Niger, Sudan, Nigeria, and beyond. The name also carries enduring cultural, ancestral, and symbolic significance to their identity.[2][20][18]

A Libyan Berber (Amazigh) author named Nesmenser published a page titled "The Temehu Tribes of Ancient Libya: Scene from the Tomb of Seti I, Dynasty XIX," in which the entire content presents misleading information and attempts to appropriate the heritage of the Tehenu, Temehu and Garamantes.[21] The Arabic Wikipedia page for أوجلة (Awjila) states that the reason for the name is based on its pronunciation: it is pronounced with an opening sound, followed by a pause, then the opening of the letters "jeem," "lam," and "ha." However, this explanation focuses solely on the phonetics of the word and does not address the true meaning or historical significance behind the name. Consequently, the origin of the name "Awjila" remains hidden or unclear to many readers because it is of Toubou origin—details which the page neither elaborates on nor permits users to correct, even when supported by reliable references. Instead, the page presents the history of the area based on the Amazigh (Berber) and Nasamones, who are considered the indigenous people of the oases, which further confirms the distortion of the history of the Toubou and their ancestors, the Garamantes. The Garamantian is NOT a barbarian civilization.

Oric Bates further critiques Herodotus’s narrative regarding the Psylli tribe since the Psylli were still in existence during Pliny’s time, hence their portrayal in Herodotus’s account appears to have been fabricated or altered by neighboring groups—particularly the Nasamones—who had occupied their lands, nearly exterminated them, and reshaped their history for political or cultural purposes.[22]

The term "Ama-Zagh" is of Toubou origin. Specifically, in the Toubou Dazaga dialect, "Ama" means "people" and "Zagh" means "camp," so the term translates directly to "camp people." While in the Toubou Tedaga dialect, a similar construction appears in the word "Zagh-na": "Zagh" still means "camp," while "na" functions as a suffix denoting people, the same resulting in the meaning "camp people." Both terms are mentioned in the Diwan of the Kanem-Bornu Empire, a key historical source that records in significant events, with entries dating as far back as the 7th century. The term "Zaghwa," referring to a Nilo-Saharan people closely related to the Toubou, also appears to share this linguistic root. In the Toubou language, "Zagh" means "camp," while "wa" is a possessive suffix, meaning "camp dwellers." Across all the Saharan tribes—including the Tuareg (Berbers)—the word "Zagh" consistently refers to a camp, with its linguistic origin goes back to the Toubou language.[23] Tamasheq (Tamashek), Tamajeq and Tamaheq are the languages of the Tuareg people, and these terms hold deep linguistic and cultural significance just like the Amazaigh language names. For instance, Tamasheq can be broken down as follows. The prefix Ta means "land" in the Toubou language, and this usage extends across all of North Africa. The term appears in expressions like Ta-Mery, meaning "beloved land," which was also used in ancient Egyptian to refer to Upper and Lower Egypt while Ma is synonymous of Ama of Toubou origin and in this context meaning "people." Finally, Sheq is derived from Zagh, which means "camp" and reflects their encampments or settlements. All of these elements of Tuareg—Jeg, Heq, and Sheq—are derived from Zagh, which the Tuareg adopted from the Toubou language.[23]

Ptolemy (c. 90–168) identified a Garamantian tribe called Tedamansi (Teda-ma-nsi), located between Fezzan and Tripolitania. The name Tedamansi can be interpreted as "sons of the Teda," where "Teda" refers to the inhabitants of Tu (Tibesti), and "ma" means "sons" in this context, while "nsi", however, the exact meaning of "nsi" remains uncertain due to limited linguistic evidence. Moreover, Ptolemy described the Garamantes as Aethiopians (Blacks), a classification echoed by several other ancient sources, as noted by Haynes[24] Ptolemy also implies that the Greek colonists had forced the Nasamones to leave the coast and take up residence in Augila.[4] Procopius, writing around 562, says that even in his day sacrifices continued to be made to Ammon and to Alexander the Great of Macedon in two Libyan cities that were both called Augila. He was probably referring to what are now El Agheila on the Gulf of Sirte and the oasis of Awjilah.[citation needed] According to Procopius the temples of the oasis were converted into Christian churches by the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I (c. 482 – 565).[4] The 6th-century geographer Stephanus of Byzantium described Augila as a city.[4]

For a long time, many historians—such as Al-Maqrizi (1360–1442) and Leo Africanus (Hassan al-Wazzan al-Fasi, 1483–1552)—believed that the Toubou were Berbers. This view echoed ancient writers’ inability and confusion, leaving both the Toubou and their Garamantian ancestors misunderstood. In addition, during his travels in the 1520s, Leo Africanus referred to the Toubou as the "Berdoa" people, also noting that they lived ten days west of Awjila—corresponding to northern Fezzan in the modern Jufra district. He also identified the Kanem-Bornu kings as Berdoa. This name derives from the town of Bardia, next to the Egyptian border, and was used by Leo to describe the Toubou.[25][26]

Early Arab era

[edit]

The Arabs launched a campaign against the Byzantine Empire soon after Muhammad died in 632, quickly conquering Syria, Persia and Egypt. After occupying Alexandria in 643, they swept along the Mediterranean coast of Africa, taking Cyrenaica in 644, Tripolitania in 646 and Fezzan in 663.[27]

The region around Awjila was conquered by Sidi ‘Abdullāh ibn Sa‘ad ibn Abī as-Sarḥ.[28] He was a companion of Muhammad and standard bearer, and an important saint. His tomb was established in Awjila around 650.[29] A modern structure has since replaced the original tomb.[3] The Sarahna family, who consider themselves the family of Sidi Abdullah, are the protectors of his tomb. When the Senussi center was established in Awjila in 1872, the Sarahna assumed the role of Islamic teachers.[30]

After being introduced in the 7th century, Islam has always been a major influence on the life of the oasis. The Arab chronicler Al-Bakri says that there were already several mosques around the oasis by the 11th century.[31] According to oral tradition, in the 12th century a learned man from the coast of Tripolitania said that there were forty shrines in Awjila, and forty saints hidden among the people of the oasis. By the late 1960s only sixteen shrines remained.[31] Some of the saints in the surviving tombs lived during the early years of Islam, and the details of their life and even their family lineage have been forgotten.[29]

Trading centre

[edit]

In the 10th century Awjila was a stage on the trading route between the Ibadi Amazigh capital of Zuwayla[a] in the Fezzan and the newly established Fatimid capital of Cairo in Egypt.[32] The east-west caravan route from Cairo to Tripoli, the Fezzan and Tunis went via Jaghbub, Jalu and Awjila.[33] In the early Mamluk era (13th century), trade from Egypt was along a route that led via Awjila to the Fezzan, and then on to Kanem, Bornu and to cities such as Timbuktu on the Niger bend. Awjila became the main market for slaves from these regions.[34] Most of these slaves supplied domestic needs.[35] Gold was purchased from Bambouk and Bouré in what is now Senegal but then was part of the Mali Empire of the Mandinka people. In exchange, Egypt exported textiles.[34]

During the Ottoman period in Egypt, Awjila lay on the route taken by pilgrims traveling from Timbuktu via Ghat, Ghadames and the Fezzan, avoiding the main Ottoman centers.[36] In 1639 Awjila came under the rule of the Turkish ruler of Tripolitania, who stationed a permanent garrison at Benghazi.[37] In the 18th century, the merchants of Awjila held a monopoly over the trade between Cairo and the Fezzan.[38] Describing the trade between Egypt and Hausaland, Hornemann lists:

... slaves of both sexes, ostrich feathers, zibette (musk from civet cats), tiger skins (sic), and gold, partly in dust, partly in native grains, to be manufactured into rings and other ornaments for the people of interior Africa. From Bornu, copper is imported in great quantity. Cairo sends silks, melayes (striped blue and white calicoes - i.e. milayat, wrappers, sheeting) woolen cloths, glass... beads for bracelets, and an... assortment of East India goods... The merchants of Bengasi usually join the caravan from Cairo at Augila, import tobacco manufactured for chewing, or snuff, and sundry wares fabricated in Turkey...[39]

Around 1810 a Majabra trader from Jalu named Schehaymah became lost while travelling to Wadai via Murzuk in the Fezzan. He was found by some Bidayat, who took him via Ounianga to Wara, the old capital of Wadai. The Sultan of Wadai, Abd al-Karim Sabun (1804–1815) agreed with Schehaymah's proposal to open a caravan route to Benghazi along a direct route through Kufra, and Awjila / Jalu. This new route would bypass both Fezzan and Darfur, states that until then had controlled the eastern Saharan trade. The first caravans travelled the route between 1809 and 1820.[40]

The trade was disrupted for a while in the 1820s due to political instability in Wadai, but starting in the 1830s every two or three years a caravan would travel the route. Usually there were two or three hundred camels carrying ivory and skins, along with a batch of slaves.[41] Trade increased from the 1860s. The main stations between Benghazi and the southern terminal at Abéché were the assembly point at Awjila / Jalu where the caravans were made up, and the center at Kufra where food and water could be obtained.[42] Later the north-south route again grew in importance due to disruption of traffic on the Nile by the Mahdist revolution in the Sudan.[40]

Muhammad ibn Ali as-Senussi stayed in Jalu and Awjila before opening his first lodge in al-Baida in 1843. Over the next ten years the lodges of the Senussi became established throughout the Bedouins of Cyrenaica.[43] Later they spread the Senussi influence further south, helping quell violence and resolve trade disputes.[44] Each post on the north-south route, including Awjila, was protected by a Senussi sheikh.[40] As late as 1907, a significant amount of the trade passing through Benghazi was in goods carried over this route, and goods would also have been routed from interior points such as Awjila and Jalu east to Egypt and west to Tripoli.[45]

Recent years

[edit]Today the main activities of the people in Awjila are agriculture and working for the oil sector companies, as this area is the cradle of Libyan wealth. The main crops are dates from the many varieties of palm trees, tomatoes, and cereals.[citation needed] The Awjila oasis is known for the high quality of its dates.[28] Starting in the 1960s, the oil industry drove growth in the once-sleepy village.[46] In 1968 the population of the village was about 2,000 people, but by 1982 it had risen to over 4,000, supported by twelve mosques.[47] A 2007 travel guide gives the population as 6,790.[48]

The Great Mosque of Atiq is the oldest masjed (mosque) in the Sahara with its unique style of architecture with rooms that are naturally air conditioned. In the scorching heat of the summer days the rooms are cool and at night they are warm.[49] The oasis was a destination for viewing the Solar eclipse of March 29, 2006.[50]

References

[edit]Notes

- ^ The medieval gate of Bab Zuweila in Cairo takes its name from Zuwayla.[32]

Citations

- ^ a b Herodotus. The Histories volume 4. Translated by A. D. Godley. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1920. Book IV, p. 173 and 183.

- ^ a b c d e Wahli, S. H. (2022, October 7). الواحات التباوية السوداء.. جنوب برقة الليبية- إقليم توزر [The Black Toubou Oases: Southern Barqa of Libya – The Tozeur Region]. Studies and Research in History, Heritage, and Languages. https://m.ahewar.org/s.asp?aid=770715&r=0&cid=0&u=&i=10076&q=

- ^ a b Ham 2007, p. 132.

- ^ a b c d e Smith 1872, p. 338.

- ^ Chandra 1986, p. 113.

- ^ Batibo 2005, p. 77.

- ^ Palmer, H.R. (1926). History Of The First Twelve Years Of The Reign Of Mai Idris Alooma Of Bornu ( 1571 1583) ( Fartua, Ahmed Ibn). p.152

- ^ W.F.G. Lacroix, Ptolemy's Africa: The Unknown Sudan, Truth or Fallacy? Publisher: TWENTYSIX; 3rd edition page 54 (18 November 2020), ASIN B08NTDVM2C, ISBN 374076824X. Language: English.

- ^ Herodotus. The Histories volume 4. Translated by A. D. Godley. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1920. Book IV, p. 172 174

- ^ Pliny the Elder. Natural History. Book 5, Sections 1–74. Translated by H. Rackham, 1952. Loeb Classical Library, with minor alterations in web version online: https://www.attalus.org/translate/pliny_hn5a.html

- ^ Hornemann, Frederick. The Journal of Frederick Hornemann's Travels from Cairo to Mourzouk... in the Years 1797–8. London: W. Bulmer and Co. see lines 108, 117 https://www.gutenberg.org/files/71426/71426-h/71426-h.htm

- ^ Hornemann, Frederick. The Journal of Frederick Hornemann's Travels from Cairo to Mourzouk... in the Years 1797–8. London: W. Bulmer and Co. see line 119

- ^ a b Bates, Oric. The Eastern Libyans: An Essay. London: Macmillan and Co., 1914. p 53

- ^ Pliny the Elder, Natural History, trans. H. Rackham, Book 5, sections §34, Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press, 1945

- ^ Pliny the Elder, Natural History, trans. H. Rackham, Book 5, sections §45, Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press, 1945

- ^ Pliny the Elder, Natural History, trans. H. Rackham, Book 5, sections §34-37, Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press, 1945

- ^ Haynes, D. E. L. (1951). An archaeological and historical guide to the pre-Islamic antiquities of Tripolitania. London: H.M. Stationery Office. p18 http://archive.org/details/archaeologicalhi00hayn

- ^ a b c d e f Wahli, S.H., 2021. The Tehenu (Temehu): Ancestors of the Toubou People… Pharaoh Shoshenq the Libyan – The Toubou. Studies and Research in History, Heritage, and Languages, 2 March. https://m.ahewar.org/s.asp?aid=710781&r=0&cid=0&u=&i=10076&q=

- ^ Palmer, H.R. (1926). History Of The First Twelve Years Of The Reign Of Mai Idris Alooma Of Bornu ( 1571 1583) see p.126 and 146

- ^ Palmer, H.R. (1926). History Of The First Twelve Years Of The Reign Of Mai Idris Alooma Of Bornu ( 1571 1583) see p.152

- ^ A Libyan Berber author named Nesmenser published a page titled The Temehu Tribes of Ancient Libya: Scene from the Tomb of Seti I, Dynasty XIX, in which the entire content presents misleading information and attempts to appropriate the heritage of the Tehenu, Temehu, and Garamantes. Link here

- ^ Bates, Oric. The Eastern Libyans: An Essay. London: Macmillan and Co., 1914. p 52 53

- ^ a b Palmer, H.R. (1926). History Of The First Twelve Years Of The Reign Of Mai Idris Alooma Of Bornu ( 1571 1583) see p.151 to see the meaning of Amazagh

- ^ Haynes, D. E. L. (1951). An archaeological and historical guide to the pre-Islamic antiquities of Tripolitania. London: H.M. Stationery Office. p19 http://archive.org/details/archaeologicalhi00hayn

- ^ Wahli, S. H. (2022, October 7). الواحات التباوية السوداء.. جنوب برقة الليبية- إقليم توزر [The Black Toubou Oases: Southern Barqa of Libya – The Tozeur Region]. Studies and Research in History, Heritage, and Languages. https://m.ahewar.org/s.asp?aid=770715&r=0&cid=0&u=&i=10076&q=

- ^ Wahli, S.H., 2021. The Tehenu (Temehu): Ancestors of the Toubou People… Pharaoh Shoshenq the Libyan – The Toubou. Studies and Research in History, Heritage, and Languages, 2 March. https://m.ahewar.org/s.asp?aid=710781&r=0&cid=0&u=&i=10076&q=

- ^ Falola, Morgan & Oyeniyi 2012, p. 14.

- ^ a b Awjila: Libyan Tourism.

- ^ a b Mason 1974, p. 396.

- ^ Mason 1974, p. 397.

- ^ a b Mason 1974, p. 395.

- ^ a b Martin 1983, p. 555.

- ^ Fage & Oliver 1985, p. 16.

- ^ a b Oliver & Atmore 2001, p. 19.

- ^ Oliver & Atmore 2001, p. 20.

- ^ Oliver & Atmore 2001, p. 46.

- ^ Holt, Lambton & Lewis 1977, p. 263.

- ^ Walz 1975, p. 665.

- ^ Martin 1983, p. 567.

- ^ a b c Cordell 1977, p. 22.

- ^ Cordell 1977, p. 23-24.

- ^ Cordell 1977, p. 24.

- ^ Cordell 1977, p. 28.

- ^ Cordell 1977, p. 29.

- ^ Cordell 1977, p. 21.

- ^ Mason 1982, p. 323.

- ^ Mason 1982, p. 322.

- ^ Ham 2007, p. 131.

- ^ Awjila: MVM Travel.

- ^ Atiq Mosque: Atlas Obscura.

Sources

- Asheri, David; Lloyd, Alan Brian; Corcella, Aldo; Murray, Oswyn; Graziosi, Barbara (2007). A Commentary on Herodotus. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-814956-9. Retrieved 2013-03-24.

- "Atiq Mosque: Early Islamic mosque with several strange conical domes". Atlasobscura.com. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- "Awjila". Libyan Tourism Directory. Archived from the original on 2013-04-11. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- "Awjila". MVM Travel. Retrieved 2012-03-24.

- Batibo, Herman (2005). Language Decline And Death In Africa: Causes, Consequences And Challenges. Multilingual Matters. ISBN 978-1-85359-808-1. Retrieved 2013-03-24.

- Chandra, Satish (1986). International Protection of Minorities. Mittal Publications. GGKEY:L2U7JG58SWT. Retrieved 2013-03-24.

- Cordell, Dennis D. (January 1977). "Eastern Libya, Wadai and the Sanūsīya: A Tarīqa and a Trade Route". The Journal of African History. 18 (1). Cambridge University Press: 21–36. doi:10.1017/s0021853700015218. JSTOR 180415.

- Fage, John Donnelly; Oliver, Roland Anthony (1985). The Cambridge History of Africa. Vol. 6. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-22803-9. Retrieved 2013-03-27.

- Falola, Toyin; Morgan, Jason; Oyeniyi, Bukola Adeyemi (2012). Culture and Customs of Libya. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-37859-1. Retrieved 2013-03-24.

- Ham, Anthony (1 August 2007). Libya. Ediz. Inglese. Lonely Planet. p. 132. ISBN 978-1-74059-493-6. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- Holt, Peter M.; Lambton, Ann K. S.; Lewis, Bernard (1977-04-21). The Cambridge History of Islam. Vol. 2A. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29137-8. Retrieved 2013-03-27.

- Martin, B. G. (December 1983). "Ahmad Rasim Pasha and the Suppression of the Fazzan Slave Trade, 1881-1896". Africa: Rivista trimestrale di studi e documentazione dell'Istituto italiano per l'Africa e l'Oriente. 38 (4). Istituto Italiano per l'Africa e l'Oriente (IsIAO): 545–579. JSTOR 40759666.

- Mason, John Paul (October 1974). "Saharan Saints: Sacred Symbols or Empty Forms?". Anthropological Quarterly. 47 (4). The George Washington University Institute for Ethnographic Research: 390–405. doi:10.2307/3316606. JSTOR 3316606.

- Mason, John P. (Summer 1982). "Qadhdhafi's "Revolution" and Change in a Libyan Oasis Community". Middle East Journal. 36 (3). Middle East Institute: 319–335. JSTOR 4326424.

- Oliver, Roland Anthony; Atmore, Anthony (2001-08-16). Medieval Africa, 1250-1800. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-79372-8. Retrieved 2013-03-27.

- Petersen, Andrew (2002-03-11). Dictionary of Islamic Architecture. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-203-20387-3. Retrieved 2013-03-24.

- Smith, Sir William (1872). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. John Murray. p. 338. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- Walz, Terence (1975). "Egypt in Africa: A Lost Perspective in Artisans et Commercants au Caire au XVIIIe Siecle by Andre Raymond". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 8 (4). Boston University African Studies Center: 652–665. doi:10.2307/216700. JSTOR 216700.

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Augilæ". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Augilæ". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.